Geof Darrow creates with torrents of nouns. Known for Eisner Award-winning, hyper-detailed and dense comic book art, most of Darrow’s work overflows from a dizzying imagination: 50s-style diners swarming with rhesus monkeys, an iguana with a pistol-nose, a gorilla-thing with dinosaur skulls braided into its hair and a titanic, flying, vomiting Donald Trump in a diaper, held aloft by a Trump-branded jetpack that looks like a leaf blower crossed with a power substation (“It was before he was elected. And he just always bugged me,” Darrow told us). Matching his mastery of infinite tiny details is his willingness to play with them, creating chimeras like hermit crab cars and dogs with knives for paws.

His recent collection of drawings, Lead Poisoning: The Pencil Art of Geof Darrow, features the pencil art before inking, including pages from his collaborations with Frank Miller, concept art from movies like the cancelled American remake of Akira and pages from his ongoing opus, The Shaolin Cowboy. After a run of issues — collected in The Shaolin Cowboy: Shemp Buffet — seeing the titular character armed with a double-long staff (tipped with chainsaws, of course), slicing through an endless horde of desert zombies, Darrow takes his avuncular martial arts master to the big city for The Shaolin Cowboy: Who Will Stop The Reign?

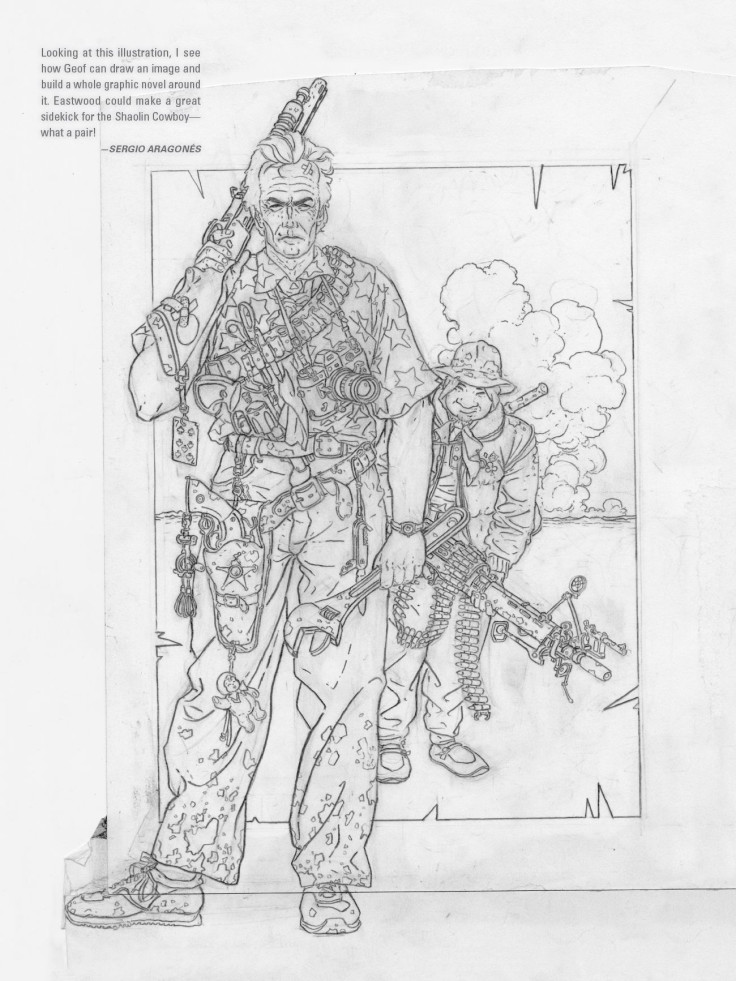

The Shaolin Cowboy comics tell martial arts stories in Western settings, allowing Darrow to play on both sides of the thin line between Eastern and Western action themes. The aesthetic is predominantly Southwestern and choked with Americana, even if the action is Shaolin kung fu. Even the Shaolin Cowboy’s costume reveals just about everything about Darrow’s multilayered approach to comic art and storytelling. Darrow pulled the cowboy’s bib shirt right off John Wayne in The Searchers.

“The colors are for two reasons,” Darrow said. “They’re the Superman colors — red, yellow and blue — and also the Chinese Superman: the Monkey King.” That’s three inspirations, each a zeitgeist-defining hero from a radically different source.

Darrow’s conceptual multiplicity is met with an equally powerful whimsy, colliding the legendary and archetypal with the goofy and irreverent. “I just put tennis shoes on him because I thought it would be funny,” Darrow said. “ I wanted to give him a cowboy hat, but I thought it would be too stupid.”

There are, of course, artistic influences Darrow would cite. He dedicates Who Will Stop the Reign? to his “ArtFather” Jean Giraud, better known as Moebius, a comic book artist who worked on Alien and Blade Runner. “That guy had more styles than Neiman Marcus had shoes,” Darrow said. “He was like a monster of drawing. He’d draw anything. Very lyrical. He was very, very nice to me.”

But, just as often, Darrow synthesizes film and TV into the blood-soaked chaos filling his pages. In short succession he cited the films of Akira Kurosawa, Lau Kar-leung, Tsui Hark, Kenji Misumi, Hideo Gosha, Bruce Lee and Yuen Woo-ping as sources of inspiration.

“The stuff that made these guys laugh, him and his crew, they would crack up when someone busted their ass. And they were always betting on shit,” Darrow said of Woo-ping, the legendary fight choreographer, who he met while creating concept art for The Matrix.

As for the Shaolin Cowboy himself, he’s “a cross between Zatoichi and Stephen Chow.” Like Zatoichi, he is a modest wanderer hiding immense power. But unlike Zatoichi, the landscape the Cowboy roams is overloaded with talkative, flashy, silly characters, like Chow’s Shaolin Soccer or Kung Fu Hustle. That makes the Shaolin Cowboy an Asian cinema mash-up roughly equivalent to recasting Naked Gun with Jack Reacher instead of Leslie Nielsen.

But what’s especially fascinating about the Shaolin Cowboy’s new adventure in Who Will Stop the Reign? is its heavy reliance on dialogue, with Darrow porting his artistic maximalism into his scriptwriting. In one encounter, the Cowboy fights a Buddhist version of the Grim Reaper, sent by the kings of hell to take his soul. There’s just one problem: hell’s warden doesn’t know the Shaolin Cowboy’s true name. Bring on the torrent of nouns. “Wang Zhengquan, Misumi, Kenji, Dragon Foot Wong, Liu Jiahui, Katsu Shintaro, Yue Sing Wai, Sacramento Yu, Shirato Sanpei, Kwan Tak Hing, Liu Chia-Liang,” the demon says. “Don Ho, Yuan Heping, Buddhist Palm and his Five Sisters Wu, Hung Kam-Bo, Siu Tin Yuen, Big Blade Wang, Wong Fei Hung…” and the list goes on, until he is defeated and cast back to hell.

Just like his art, Darrow’s Shaolin Cowboy dialogue is stuffed with references, in this case a cavalcade of martial arts figures, including actors, directors, manga artists, choreographers and the legendary figures that inspired their movies. Yes, the Zatoichi actor, Shintaro Katsu, is named too.

“A lot of times I don’t even remember what I wrote and I’d forgotten I’d done that,” Darrow said. “I just knew the guy had to rattle off a bunch of names before Shaolin Cowboy busted up his soul jet or essence and sent him back to hell.”

It’s a huge contrast to the mostly silent Shaolin Cowboy in Shemp Buffet, who fights with only the chainsaw sound effects and occasional grunt cluttering the action. He described it as an intentional contrast with the “Marvel style, where Spider-Man is talking through a whole fight.”

“It’s all a fantasy, so I guess it doesn’t make sense to think it through all that much, but when you’re fighting these guys you’re not going to have time to be like ‘Here’s sand in your eyes, Sandman!’” he said. “I thought it would be funny for it just to be him.”

His most common answer to questions regarding artistic inspiration is “I thought it would be funny,” so it’s no surprise Darrow described the voluminous dialogue as an exercise in defying expectation. “I thought for the next one they’re going to be waiting for me to do more of the same,” he said. “So I thought I’d put a little more.”

Though his writing demonstrates all the same meticulous abundance as his art, Darrow hesitates to describe it as anything but utilitarian. “I always think of like Jack Kirby, where you have a plot and you just have to draw it and then you say ‘Oh, well, someone has to say this or that,” Darrow said. “I wrote a screenplay for The Shaolin Cowboy movie when I was in Japan. And that’s the first time I had to sit down and write a story out before I drew anything. You guys, you writers, it’s a lonely, lonely job. It drives me crazy. I can’t listen to music or have television on.”

(The Shaolin Cowboy movie!? “Sitting in boxes in Japan, half-finished,” Darrow told me. Oh. The Weinstein Company was supposed to co-produce, but they pulled out. “His face is like a walking Picture of Dorian Gray,” Darrow said of Harvey, “every sin is carved into that ugly mug of his.”)

Though Darrow is casually self-deprecating about his work, little moments of enthusiasm reveal the rigor behind it. “I can make stuff up, but if they’re based in reality, the craziness works more,” Darrow said.

His mastery may come from overwhelming details, the kind of stuff that makes his comics endlessly re-readable, Darrow boils his objective down to something simple. It involves, a reference, of course, this time to Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure. “My favorite line is, he comes up at the end and there’s the prison bus and he comes up and goes ‘What do you think?’ and a prisoner goes ‘Action Packed!’” Darrow said. “That’s my goal. Make it action packed for Pee-Wee.”