We are the people we are today because of the cartoon shows we watched as children. It doesn't matter if you are pushing sixty and loved the Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle, or you're a teenager who only watches Egoraptor on YouTube, everyone watched cartoons.

The first animated television show was Crusader Rabbit, which first aired in 1949. It was the story of a rabbit and his tiger sidekick, defending others against injustices in the world. The visuals of the show were extremely simplistic, with very little frame-to-frame animation. Characters’ mouths wouldn’t line up to dialogue and there was very little actual movement on screen.

Before Crusader Rabbit, the only way you could see cartoons was in the movie theater. Disney and Warner Brothers created gorgeous and highly detailed shorts and films all drawn by hand.

Crusader Rabbit was created by Jay Ward, who later went on to change the industry with Rocky and Bullwinkle. Ward, along with other Hollywood animators, set the precedent of how animation for television would be created for the next three decades.

“They decided that the way the animation was going to be seen, didn’t have to emphasize the visual idea, doing it frame by frame, painting in each frame, wasn’t necessary, so they could come up with a different type of animation, called limited animation” Ron Simon, curator of Television and Radio at the Paley Center For Media, told iDigitalTimes.

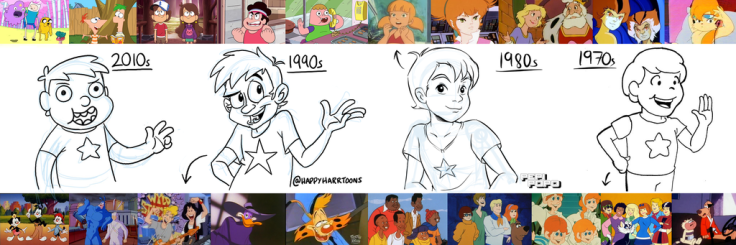

Most animated television shows from the 1950s to 1980s used limited animation techniques. Animated television shows are created for the medium that people are watching them on. Simon says that “90’s cartoons, with their fluid animation and gorgeous colors and visuals came around because of the big screen television.” Dexter’s Laboratory and Batman: The Animated Series used motion to tell a story, which really wasn’t an option for previous generations of animators.

“In the 1950s and most of the way through the 1960s, most people had black and white television sets, so the visuals didn’t matter, so the animators intuitively knew that people were responding to the sound,” Simon said. The creators drew and created these series in color, but most people just ended up seeing them in black and white.

“Most of the audience had a taste for radio, filled with great vocal talent,” Simon explained. “Viewers were filling in the animation with color with their imagination, so it was a television experience and a radio too, your mind was completing the picture that the animators really didn’t have to fill in.” People seemed to be responding to the sound more than the actual animation.

Unlike Disney’s feature-length films, limited animators were “trying to make their characters more identifiable, rather than making a beautiful frame where every frame was different.” They did this by focusing on wordplay and jokes.

“People like Jay Ward or Hannah Barbera were trying to appeal to both children and adults with sophisticated wordplay throughout, it had a sophistication many of the Disney films did not, they were really looking for this ongoing character chemistry, they weren’t looking to draw in the entire frame, but really concentrate on the lead characters and how they connected with one another.”

Hannah Barbera shows, like Scooby Doo, appealed to both parents and children. “The main objective was to create good characters, good interaction, interesting situations that gave a cartoon the possibility to run for years.”

Limited animation is making a comeback. Computers have made reusing assets, or previously drawn pictures, necessary. There’s no need to draw The Simpsons frame by frame anymore. The internet has allowed one guy with a vision to release a short or video straight to the public using everything Jay Ward, Hannah Barbera and so many more pioneered.