Our not at all timely coverage of The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask continues. See also Part I, Part II, & Part III.

The Gameplay and the Narrative in Harmony

The gameplay mechanics and the story of Majora's Mask suffer these kinds of problems for most of the game's length. This is all the more frustrating because the game's most important mechanic is in perfect sync with the storyline, casting a stark shadow over the problems elsewhere.

That mechanic is the Ocarina of Time, and that storyline is the destruction of Termina at the end of Link's third day in the world. It's the core conflict of the game: the Moon will destroy Termina in three days unless Link can stop it, but Link can't stop it in three days. That conflict is the source of the game's prevailing mood of despair and ruin.

But the Ocarina of Time, which Link acquired in the eponymous game, allows Link to travel back in time. By three days. To the beginning of the cycle. So, although there is no way at first for Link to stop the Moon, he can always return to the beginning of the first day through the gameplay mechanic of playing the Ocarina.

When Link does so, and he must do so often, the entire world resets to its original state. Townspeople reappear. Regions of the world return to their corrupted state. The dancers Link taught to dance forget how to dance. All of Link's progress in the world is for nothing. But the Ocarina staves off the Moon for three more days.

Only one thing changes with each cycle. Link keeps new items and masks he has acquired. These allow him to progress incrementally even as the world cycles from worry to despair, danger to doom, over and over again. Link advances ever so slightly while the world around him remains frustratingly the same. The player feels what the townspeople in Termina feel: despair, frustration, powerlessness, with the merest glimmer of hope.

And that's enough. That perfect sync, more elegant than The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time's seven year time travel, makes The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask so satisfying and memorable.The game and narrative fail in other areas, but here they are perfect, and it is clear that the entire game was designed with the time travel mechanic in mind.

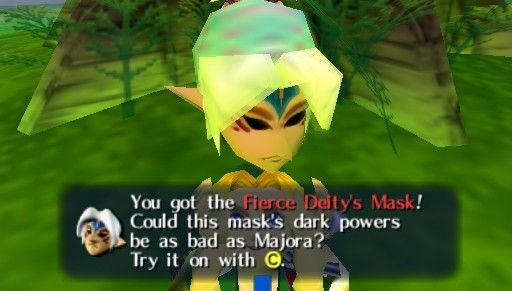

Other, smaller moments, like the mission to protect a Milk Cart from the Gorman Brothers, and the acquisition - but not the usage - of the Fierce Deity Mask similarly blend gameplay and story in a compelling way. They aren't nearly as integral to the story, but they stand out, even if you're playing the game for the first time. That's because, even to the most casual player, events and situations where gameplay and story elements work in harmony tend to be memorable. They are the best of what gaming can be, and dedicated players flock to such experiences.

Despite its flaws, despite so many areas where the gameplay and the storyline do not work well together, Majora's Mask is a great game and great art. It has one of the best stories and worlds of any game of its generation, and it meets or exceeds the gameplay standards set by its predecessor. But the flaws in the game do prevent it from reaching the highest pinnacle: a game as art. Each element excels individually, but together, most of the time, they fail. So Majora's Mask remains a far cry from perfection, despite all its successes.

If only we could play the Ocarina of Time, and give Majora's Mask one more chance to change.