Hundreds of sweaty concertgoers are waiting patiently in the baking sun. But they're not seeking respite from the 95-degree heat in one of Panorama's many cooling tents. They're not posting up to see Arcade Fire or Kendrick Lamar or LCD Soundsystem on the main stage, either. They're interested in a different kind of hype, one that spread like wildfire on Randall's Island this weekend. They're here to see "The Dome."

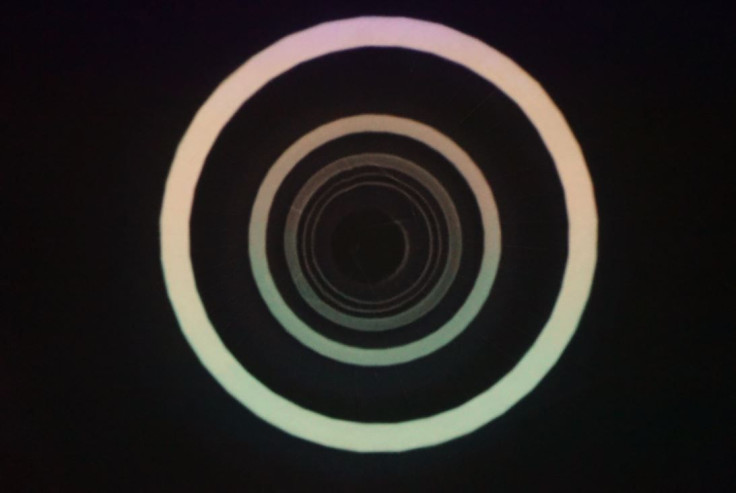

The Dome (officially The 360 Virtual Reality Theater) was a VR art installation built for Panorama. It wasn’t just the structure itself (which, believe it or not, was set up in just a day) that attracted music lovers. Three-dimensional caves, whirling light rings, and rumbling acoustics captivated the hundreds of sweaty bodies lying side-by-side on the floor of the 70-foot structure.

BoBo Do and Nicholas Rubin worked closely together at their Brooklyn-based projection design studio, Dirt Empire, on The Dome. They’re no strangers to big projects; they once mapped the interior of the UN for Beyonce, but this was a unique opportunity.

“It’s not normal square content. You don't have people locked down sitting looking at one thing. It’s not just their eyes traveling. In a dome, you’re whole body has to move to get everything. You can make mountains feel like big mountains, you can make giants and canyons feel vast but you have to know where to situate them within the sweep of the hemisphere for the illusion not to break down,” Rubin told iDigitalTimes.

Outside of museums and planetariums, very few have had a chance to experience such an immersive art. This type of three-dimensional storytelling is still a relatively new idea, even for the three studios that produced it. The dome, situated in a huge exhibit dubbed ‘The Lab’ (curated by META.is and presented by The Verge ) was a case study to bring technology-driven art into the festival world. It proved successful, but it was a particularly challenging project for everyone involved.

Dirt Empire visually produced the content alongside Elliot Blanchard of Invisible Light Network, an integrated creative studio specializing in interactive motion design.

“How do you structure motion in a dome environment as opposed to on a flat screen?” said Blanchard. “There are certain things you do to tell a story; you have cuts, change camera angles. Here it's a totally different environment. If you move things too much, people will get sick.”

Testing out their content was a challenge of its own. Without having the physical structure to preview their work, Do, Blanchard and Rubin found a way to build The Dome in VR. Just a week before the festival, a test dome was set up in Greenpoint.

“We had Vive headsets to watch the film while we worked on it. We needed something that was in scale so we could see what people field of view was,” Blanchard said.

While the visual images may be most memorable, the experience would have been incomplete without the help of Antfood, the audio studio that produced The Dome’s original score. Creative Director Wilson Brown worked closely with Blanchard, Do, and Rubin to make their story feel like a fluid composition. Brown and his team used a technique called third order ambisonics, an elaborate mixing process that gave the dome a fully immersive experience.

“It allows us to mix in a hypothetical sphere. We had this 3-dimensional spatial sound that was mixed and would bounce swirl or twist around the dome,” Brown said.

The film was broken up into multiple sequences. Generally speaking, Invisible Light Network is responsible for the first half, and Dirt Empire the second. It was Antfood’s contribution that really tied everything together. Brown said one of his favorite parts is the light rings bridging into the leviathan scene.

“Musically and sound design-wise there are two things that are successful. One, the light rings are so simple and captivating. We had just a simple little swell every time the light passes by you, you get a ‘Vmm’ that shakes the floor that everyone was lying on. Then, it opens up into this world where there's a big giant monster standing above you. There are these big sound design footsteps, but it has a nice chord progression that pulls you along musically,” Brown said.

Do describes the overall concept as “different scales of the universe,” drawing inspiration from Eames’ Power of Ten from the 1970s, where they zoom from the molecular level to the cosmic level.

“It was supposed to be a journey through various octaves of reality, ones that people can't necessarily see -- like vibratory realms, geologic realms, and human realms,” Rubin added. “We have some Buddhist undertones in the content. It’s fairly apparent if you watch. There’s some Buddha faces and a sky burial ground in one scene.”

Blanchard’s interpretation is a more emotional experience. He views the progression as a journey of becoming.

“We move from a very safe environment to a cave, which is also sort of a womb-like underground environment with the birds echoing and then you’re kind of shot out of it into this world that’s challenging,” Blanchard said “Then by the time you get to the cities, you’re kind of alone and there are arrows raining down on you. It’s a very threatening. That’s our section on the challenge of life.”

That’s when the dancers come in, which Blanchard describes as the first feeling of community.

“They are these mysterious figures but they’re friendly and coming toward you. The leviathan is the idea of you meeting the other, but you’re prepared for it. The rest of the film is about you working on yourself in an abstract space.”

Throughout the 12-minute show, festivalgoers cheered and clapped with excitement. Some even came back a second time.

“For us doing stuff mainly for animation, we never have an audience. People may like our video on YouTube or write a comment; this is cool because you can sit with the audience and hear their reactions," Blanchard said.

With the many hours spent creating the dome experience, Blanchard, Rubin and Do want to figure out a way for people to watch after the festival. There’s talk of licensing the content out for other domes, pitching the dome to a new festival or even making the experience available for VR headsets like Google Cardboard. Sweaty concertgoers not included.