Last Friday, researcher Pedro Vilaca confirmed Mac computers as the newest addition to the vulnerable BIOS club. In a recent blog post, the security researcher revealed Macs shipped prior to the summer of 2014 are vulnerable to BIOS exploits that allow for backdooring into a machine at the lowest hardware level.

Utilizing Vilaca’s attack method, hackers have the ability to completely overwrite the firmware that boots up the computer and loads the operating system. Once the machine is infected, there is no remediating, as it operates below protections like the antivirus or other security products, taking control of the system from the very first instruction. Being placed at the lowest levels of a computer’s boot chain also renders the malware completely undetectable so that it could live silently below your operating system for years.

The vulnerability Vilaca discovered is exploited in the sleep mode of Macs more than a year old. To execute the attack, all a hacker needs do is point a victim to a malicious website through phishing or other method, and remotely install the malicious firmware on a Mac computer. Then once the computer wakes from a period in sleep mode, the firmware executes, installing deep into the lowest levels of the computer. Once installed, the firmware is completely resistant to hard drive reformatting or reinstallation of the operating system, rendering the victim helpless to resolve the issue.

While a related BOIS attack method known as Thunderstrike was revealed earlier this year, Vilaca’s new attack method proves more threatening as it can be executed remotely, requiring no physical access to the victim’s computer itself. This means your attacker can be located virtually anywhere in the world and still compromise your machine.

So how does Vilaca's exploit works? It starts with your Mac going to sleep. When your computer “wakes up” from sleep mode it is then that the attacker has his in.

Here’s why.

Under normal circumstances, Apple computers have a protection in place called FLOCKDN. This allows userland apps very limited read-only access to the BIOS region of the computer. This means those apps don’t have the power to overwrite the BIOS firmware, only read it. For some reason though, that protection is oddly deactivated when a Mac wakes up from sleep mode, leaving the firmware open to be rewritten or reflashed. From there, the attackers can completely overwrite the existing firmware and program its own low-level functions that execute before the operating system even begins booting. While finding exploits that could allow for complete “root” access to MAC OS X’s resources has often been thought to be quite difficult, according to Vilaca, hackers could utilize a drive-by exploit planted on a malicious or compromised website to start the BIOS attack.

"The bug can be used with a Safari or other remote vector to install an EFI rootkit without physical access," Vilaca wrote. "An exploit then could either verify if the computer already went previously into sleep mode and is exploitable, it could wait until the computer goes to sleep, or it can force the sleep itself and wait for user intervention to resume the session."

Very few users would become suspicious that they were under attack if their computer suddenly went into sleep mode, so the attack for the most part could happen without any awareness on the part of the victim.

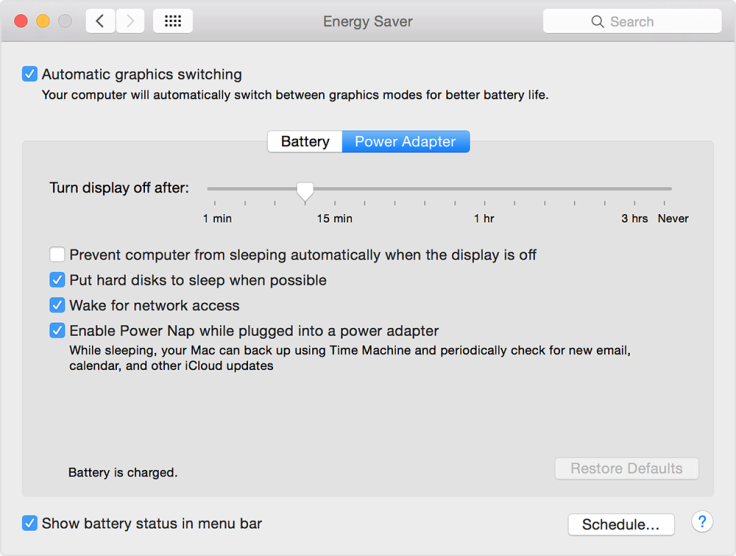

At this time there aren’t any options available for patching the problems in vulnerable Macs other than to change default OS X settings that put machines to sleep, said Vilaca. Though there is some advanced software available here and here, that allows users to dump the contents their Mac's BIOS chip and compare against Apple firmware files to detect if an attack has occurred, there is no safeguard currently against these kinds of attacks. The fact that Vilaca released his research prior to notifying Apple of the bug has raised a few eyebrows, but Vilaca says his hope is that outing the issue will make “OS X better and more secure.”

According to Vilaca the Mac vulnerability he’s found is not likely to be used extensively in the wild, but it may prove to be a useful attack method for specific and targeted attacks.

While this newly discovered bug in Mac low-level hardware may seem alarming, it just makes Mac yet another of the many systems which are vulnerable to remote BIOS attacks. In a presentation at Hack in The Box security conference in Amsterdam last week, security researchers Xeno Kovah and Corey Kallenberg demonstrated attacks on a variety of machines – both with physical and remote access.

Utilizing a malware they’ve named “LightEater”, the researchers demonstrated how they could use BIOS vulnerabilities to break into and take control of the system management mode of a computer. Once the SMM is compromised, attackers can install rootkits and steal passwords and other data from the system. The malware also allows attackers to read all data and code that appears in a machine’s active memory.

While this level of access has many implications, one of the most important is that it allows attackers to undermine even computers using the Tails operating system -- the system Snowden raved about as the secure method through which he and journalist Glenn Greenwald orchestrated the NSA document leaks. Because low-level access allows attackers to read data in memory, the encryption key of a Tails user could be read and used to unlock encrypted data or access sensitive files when they are brought into memory.

The machines compromised in Kovah and Kallenberg’s demo didn’t include Mac computers, but duo are scheduled to present at Defcon 2015 along with Thunderstrike discoverer Trammel Hudson, where they will showcase the many ways that Apple computers are vulnerable to the same firmware attacks affecting PCs.

According to Kovah and Kallenburg, BIOS vulnerabilities run rampant in virtually every system on the planet. While there are some patches available to fend off malicious attacks, alarmingly, very few people apply them, despite the ease through which patches can be installed.

“The problem with BIOSes essentially, is that they have gotten too reliable for their own good,” Kovah told iDigitalTimes. “Back in the old days people were aware of BIOSes and they did have to update them occasionally because there were bugs and stuff that inhibited them functionality wise. But in the last 10 or 15 years, we come to rely on the fact that very few people have to fix just bugs in the BIOS anymore. So, in some sense, IT organizations have kind of ‘forgotten’ about BIOS because their last experience with it was 10 to 15 years ago. It’s just not something that’s on their radar.”

For Kovah, the lack of interest in patching vulnerabilities in BIOS is disconcerting as it causes responsible disclosure to backfire and ultimately leave users more vulnerable than before the weaknesses were publicly outed.

“We’ve done the right thing,” said Kovah. “We’ve told the vendors of these weaknesses and the vendors have patched them, but then no one ever applies them. Responsible disclosure kind of falls on its face if I begin to create patches and I tell everybody, ‘hey there’s these new vulnerabilities you gotta patch them’ and then nobody patches it. Then all I’ve really done is tell attackers ‘hey there’s this big vulnerability out there and you can attack it’.”

![[EG April 19] Best 'Stardew Valley' Mods That Will Change](https://d.player.one/en/full/226012/eg-april-19-best-stardew-valley-mods-that-will-change.png?w=380&h=275&f=955520b8313253ee3c39c791f6210f38)