When Google bought DeepMind in 2014 it was investing in the cutting edge of artificial intelligence (AI) research, a company seeking to “combine learning and systems neuroscience to build powerful general-purpose learning algorithms.”

Details on Google and DeepMind’s work into AI were scant until this week, when science journal Nature revealed what the AI research firm was up to in a paper titled “Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning.” The paper reveals that the DeepMind AI has been busy learning the ins and outs of Atari 2600 video games. The big lesson so far? The Artificial Intelligence of DeepMind may be good at Space Invaders, but we’re still a long ways off from Artificial Intelligence gamers.

Google DeepMind AI Playing Space Invaders

The Nature paper and its 19 co-authors — including DeepMind founders Demis Hassabis and Shane Legg— demonstrate the strength of reinforcement learning in developing programs that can teach themselves to fulfill human-set objectives. In this case, the DeepMind artificial intelligence, described in the paper as “a deep Q-network,” ran multiple, randomized attempts at success in the game, essentially “evolving” better and better skills through repetition.

The DeepMind AI found great success in games like Space Invaders, Breakout, Fishing Derby, Freeway, Stargunner, Crazy Climber, Kung-Fu Master, and Robot Tank. In many of the Atari games the DeepMind AI far surpassed the best human players. Still, the AI proved inept at a number of other video games, including Ms. Pac-Man, Private Eye and Montezuma’s Revenge.

The DeepMind AI fails at certain video games for a number of reasons. MIT Technology Review highlights the AI’s inability to “make plans as far as even a few seconds ahead.” The DeepMind AI has a similar inability to discover and apply new principles to new situations. Unlike human gamers, who can take facility in one game and port those skills to another, current AI lacks a capacity to build the same meta-cognition principles -- to think about thinking and adjust -- that make human thought so flexible.

Google DeepMind Co-Founder Shane Legg on AI Threat

The gaming failures of the Google AI highlight the immense gap between the promise of AI and its reality today. While the conflation of current artificial intelligence technology with human-like intelligence is largely the fault of a media misrepresenting the actual state of the art in artificial intelligence research, it is also easy to imagine how AI companies like DeepMind benefit from stories that confuse complex and powerful algorithms for nascent human consciousness (Loenid Bershidsky of Bloomberg has more on how tech companies can benefit from “AI hype of the worst kind”).

AI Warnings Overblown

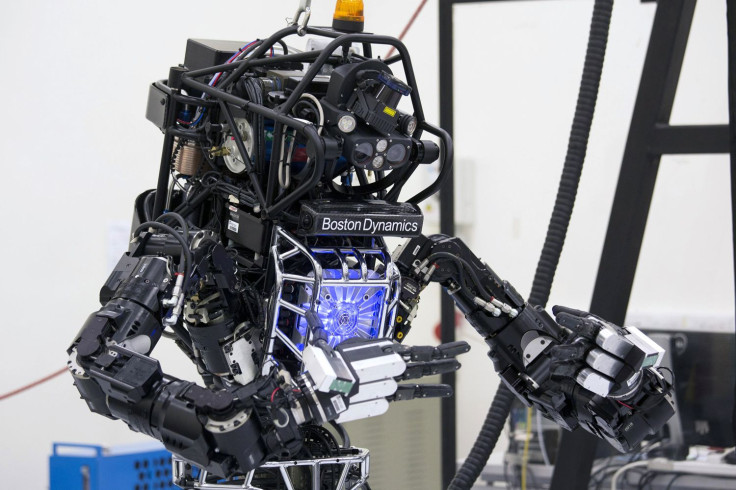

Despite headline grabbing warnings from public figures like Elon Musk, Bill Gates and Stephen Hawking, an iDigitalTimes interview with Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) roboticist Dr. Gill Pratt reveals the need for caution in our estimation of artificial intelligence, particularly in robotics fields that are so often distorted into apocalyptic scenarios in the popular imagination.

“[There is a] tremendous amount of press by luminaries of various sorts in a number of different fields saying ‘hey guys we all have to watch out because we might end up building systems that then doom us in the future,’” Pratt said. “I respect a lot of those thoughts, but at the same time there’s this tremendous gap between the capabilities we have now and the concerns that are being expressed. And so, the concerns are legitimate at some point in the future, but I think it’s important to make sure that we understand how big of a gap there is between the capabilities we have now and the worries they have for then.”

While Pratt was speaking on AI threat generally, the DeepMind video game demo is our best evidence yet that Musk’s warning that "the risk of something seriously dangerous happening is in the five year time frame…10 years at most,” may be overblown. Musk emphasized his fears were not constrained to the “narrow” AI exemplified by systems like Siri, which depend upon complex sorting algorithms and immense data sets to give the illusion, however imperfect, of interaction with a human-like intelligence. Rather, Musk invested in DeepMind not for a return but “just to keep an eye on what’s going on with artificial intelligence.”

According to Musk, who raised alarms in the comments of an interview with AI skeptic Jaron Lanier, “unless you have direct exposure to groups like DeepMind, you have no idea how fast... it is growing at a pace close to exponential.”

Pratt, though not addressing Musk’s warnings specifically, would seem to disagree. There is a line between increasingly sophisticated perceptual and learning systems and the human-like consciousness to which we imagine AI research leading, he explains.

“What we’re beginning to learn to do is to build a perception system in a robot that can begin to recognize the same sort of things that people do,” Pratt said. “These machines now can recognize things and know the difference between a soda bottle and a pair of glasses when they look out on the world, but they don’t know what the purpose of the soda bottle is, they don’t know the purpose of the glasses. They don’t know what you can do with these items.”

The Atari “reinforcement learning” applied to Google’s DeepMind AI is indeed an impressive feat and an expansion of our capacity to build machines that can solve problems based on loose parameters for success. However, it is not yet approaching the uncontrollable “demon” feared by Musk, or the “computer that thinks like a person” promised by AI start-up Vicarious’ co-founder Scott Phoenix. Perhaps Gates and his less dire vision of an AI threat in “a few decades,” is the better benchmark.

The Promise of AI

Understanding both the promise and limitations of the Google DeepMind AI research is integral to crafting our future relations with machines. Too many headlines are taken up with an imaginary AI threat that can obscure societal considerations about the ethical application of computing power to human fields. As Lanier put it, “if AI was a real thing, then it probably would be less of a threat to us than it is as a fake thing. What do I mean by AI being a fake thing? That it adds a layer of religious thinking to what otherwise should be a technical field.”

Pratt is more pragmatic and emphasizes transparency.

“I think scientists and engineers owe the public and people who think about ethics a very honest description of the state of the art,” he said.

![[EG April 19] Best 'Stardew Valley' Mods That Will Change](https://d.player.one/en/full/226012/eg-april-19-best-stardew-valley-mods-that-will-change.png?w=380&h=275&f=955520b8313253ee3c39c791f6210f38)