Disease wastes us, rots us, expends the body’s normal energy on tumorous tissue, wears us down and leaves us oozing contagion and fluid. Most disease is messy and protracted. Even the common cold lingers. So we whisk away excretions, counterbalance disease with cleanliness and contrast the death underlying disease with the color white. So much of sterility is psychological and social. We expect a doctor’s office to be clean because we can’t bear being reminded of the messiness disease brings to our bodies.

But what happens when disease is everywhere? Where can we cloister ourselves when the entire structure of our society produces illness, when it’s our lives that are diseased? These are the foundational questions of A Cure for Wellness, which pits the societal sickness of modernity against a more traditional horror evil, mashing body horror and gothic dread into a poultice of paranoia and fear.

A Cure for Wellness opens with one stressed-out finance apparatchik dying from a heart attack, another retreating to “take the waters” in a remote European clinic and a third young go-getter, Lockhart (Dane DeHaan), stepping up to bat in their cutthroat corporation, so blinded by ambition that he carries his detachment and alienation into his dying mother’s sickroom. The board of his company demonstrates their diseased mentality early, both admitting to rampant financial illegality while simultaneously threatening Lockhart with his own portfolio peccadillo. Everyone is guilty and every interaction is just a barely masked effort to pass the virus on. Lockhart will be made to take the fall, unless he can retrieve Pembroke (Harry Groener) from the clinic high up in the Swiss Alps.

Psychologist Oliver James argues in The Guardian that capitalism itself (or it’s more virulent form, “selfish capitalism”) has lead to a “startling increase in the incidence of mental illness in both children and adults since the 1970s.” He diagnoses our society with an ongoing delusion that places the blame for capitalism’s evils on each individual. “If you don’t succeed, there is only one person to blame,” our economic superstructure says, engaging us in the ongoing lie of a perfect meritocracy. “Depressed or anxious, you work ever harder,” James writes, “ or maybe you collapse and join the sickness benefit queue.” The stresses of society warp our self-perception, mutating into illness that leaves us grasping for a cure and spiraling toward death.

Lockhart has been ordered to step out of normal society, which makes him an anomaly at the clinic. Here’s a man who doesn’t yet know what the in-patient CEOs, titans of industry and accomplished diplomats have discovered: we’re all sick. And so their feverish pursuit of a definitive cure to an indefinable disease raises some alarms for Lockhart (and us).

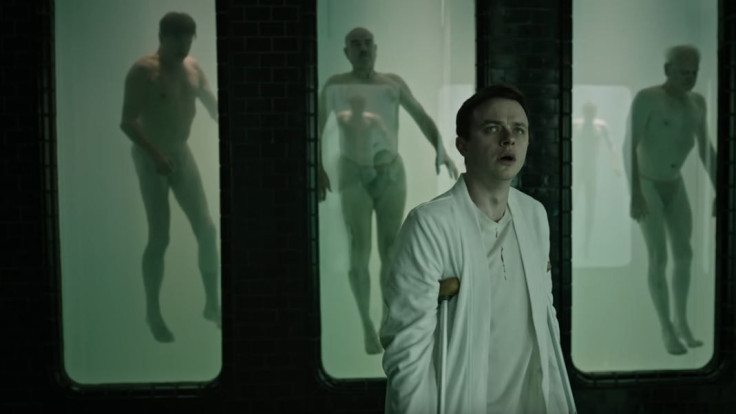

Once we’re trapped in the clinic with Lockhart all sorts of strange, disjointed things start happening. The water is full of larva, the sensory deprivation tanks infested with eels and bodies are borne off to mysterious underground caverns. There are moments in A Cure for Wellness that will have hardened gorehounds cringing or laughing maniacally at just how long director Gore Verbinski dares to linger on torturous dental surgery. And the oddities go beyond the horrific — A Cure for Wellness embraces pulp, gothic foreboding, eccentricity and camp. There’s a fairly significant subplot about crossword puzzles, a lot of geriatric water aerobics and some euro-goth techno club kids right out of Run Lola Run.

This menagerie of strange sights and sounds might be part of the problem as well. A Cure for Wellness has style and tone, but little focus. While Lockhart’s nightmarish journey into paranoia and disease (his teeth begin to fall out) is undeniably effective, a lengthy excursion into a townie bar pop the gothic oppressiveness of the castle clinic. The movie’s central medical mystery is engaging, but its villain less-so, depending upon awkwardly inserted snippets of history lesson exposition about the castle’s violent 200-year history.

The eventual object of Lockhart’s quest, Hannah (Mia Goth), suffers most of all. Infantilized to the point of dramatic inertness, dragged around by Lockhart or shut in a room by clinic director Volmer (Jason Isaacs), the third spoke in A Cure for Wellness ’s dramatic wheel has no motive of her own and barely sufficient agency for us to believe she wants anything at all. As a consequence the power play between Lockhart, the cutthroat capitalist, and Volmer, the keeper of aristocratic Old World mysticism, has no real target. Hannah is analogized to a toy — a dreaming ballerina given to Lockhart by his mother — and suffers in the comparison. That A Cure for Wellness ends with Hannah’s awakening into a world outside of Volmer’s control finally gives her a point, but does nothing to plug the holes her under-development leaves in the preceding hours.

While we share Lockhart’s bewilderment, A Cure for Wellness often shares with us his frustration as well. For as effective as Wellness can be, it’s also occasionally boring, wending circles through the clinic halls and doling out revelations in discrete chunks. The narrative disjointedness feels dream-like at its best and meandering at its worst So while A Cure for Wellness is loaded with memorable horror moments, it fails to build to a crescendo or catharsis, like a fever that never quite breaks into a moment of clarity or sinks fully into dread and death.