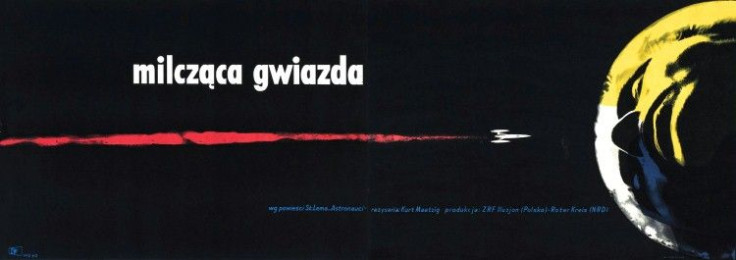

You see a rocket. It’s small, with two rounded nacelles mounted on a white, needle body. It’s a craft fit for Duck Dodgers and his far-flung future century (and a half). While the rocket is iconic Googie, the red exhaust trailing behind it is formless, a fat splash of neon blood across a landscape movie poster. The ship is on a collision course with a planet of swirling, colored gases. Look closer and you’ll realize the planet is actually an immense human face, seen from beneath and wreathed in shadow, its eyes closed in repose.

The poster is for a 1960 East German / Polish science fiction film called Milczaca Gwiazda, which translates to Silent Star, though it was ultimately released in the United States rechristened First Spaceship on Venus with a truncated edit. Mystery Science Theater 3000 made fun of it. I’ve never seen the movie.

It hangs above my TV. The transformation of space exploration into a personal journey, as the rocket flies into the alien landscape of a human mind, captures some essential part of science fiction for me. That we go out into the unknown and find ourselves has always been an enduring sci-fi theme, but it found its most operatic and moving expression on film in movies like Time Masters, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Solaris, The Matrix, Stalker, Planet of the Apes, Forbidden Planet, Starship Troopers and Star Trek.

The poster for Milczaca Gwiazda has come to stand for all of those movies and for those nights spent tense, paperback in hand, as the Moties swarm from the MacArthur to the Lenin, as rioting breaks out in the name of Adam Selene, and as animals rain from the sky in Kim Stanley Robinson’s 2312.

A movie poster can crystallize so much of what matters to us, sometimes even without its movie. Which is good, because so much has been lost.

It’s estimated that only half of American sound films from before 1950 survive to the modern day. The survival rate for silent film is even lower, with Martin Scorsese’s film preservation organization, The Film Foundation, claiming over 80 percent of films made before 1929 are “lost forever.”

It took decades for film preservation to become a priority (many film prints continue to be neglected, check out our visit to the American Genre Film Archive), so it’s easy to imagine how much more dire the situation is when it comes to artwork whose only purpose is marketing.

Bruce Hershenson, founder of movie poster auction site eMoviePoster, explained the scale of loss, telling iDigi, “Through 1915 to 1940—that’s 25 years—they never saved anything. You think someone would be like ‘we should save one of everything we do.’” Movie posters are by their nature a disposable medium, and many theaters never hesitated to toss them away.

That’s changed in recent decades. Today, poster collecting is a substantial business. What started as little more than a minor collector’s hobby tucked into the corner of comic book conventions soon became a multi-million dollar feeding frenzy. “I did an auction in 1990,” Hershenson said, “it took in over $900,000.” That was just the beginning. “It just grew and grew and grew. I was doing well over a million dollars a year in the 1990s.”

Just like the first appearance of Superman in Action Comics #1, which grabs headlines every time an issue goes up for sale, poster collecting soon attracted its fair share of speculators. A King Kong one-sheet sold for $97,000, while posters for Fritz Lang’s silent, sci-fi classic, Metropolis, have taken in over half a million.

Still, the movie poster market is a ways off from the rampant speculation currently blowing up the art world and converting thousands of paintings into in-storage alternative investment vehicles for hedge funders. “1% of the posters are $10,000 or more that’s what everyone focuses on,” Hershenson says. “But really the heart of the hobby are posters that sell between $25 and $500. That’s the heart of it. That accounts for 90% of the hobby.” Movie posters are still personal.

This is in large part because posters, unlike other forms of art, often have a direct attachment to the collector’s life. “You collect your own personal memories. There are a few people who collect ancient coins... but mostly people collect memories. It tends to be what they loved as a kid or what they loved as a teenager,” Hershenson said.

“The prime collectors tend to be around 40 to 50 and they buy stuff from about 20 years earlier,” he said. This means that “the hottest, most popular posters tend to be from the 1970s, because the people who buy have money to spend tend to be in their 40s and 50s.”

“Right now it’s like Star Wars , James Bond, Clint Eastwood, spaghetti westerns and Dirty Harry. Give it another 5-10 years and it will be Arnold Schwarzenegger, everything just keeps moving forward.”

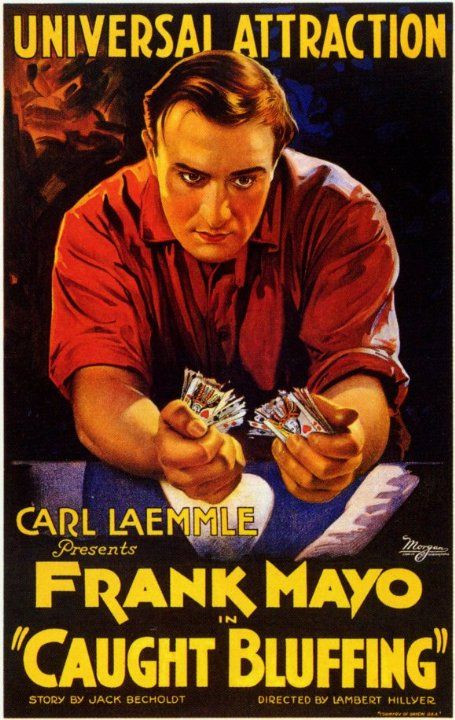

Nostalgia and personal attachment can be a powerful motivator. Hershenson named a poster for the 1922 silent film Caught Bluffing as a personal favorite because of his past as a professional gambler.

Poster collecting also depends on more subjective, aesthetic judgments. Many movie fans lament the rise of the “floating head” poster, for which Photoshop is often blamed. But Hershenson claims the rise of the floating heads began back in the 80s, calling it “a sad turn.”

“In the 20s and 30s everything was art. They’d hire artists and do wonderful stuff. They had pin-up artists and illustrations. Great people. Starting in the 1940s they wanted to save money. It wasn’t The Depression. Really it was World War 2, because they stopped showing their movies all over the world,” Hershenson says. “So they switched to photographic posters. But that still wasn’t bad. In the 50s there was some great stuff.”

While modern movie posters may overindulge in floating heads, saturated yellow, butt shots, poor text treatments and dudes shooting hard stares over their shoulder, the rise of movie poster collecting has nurtured some major compensations, like Mondo posters.

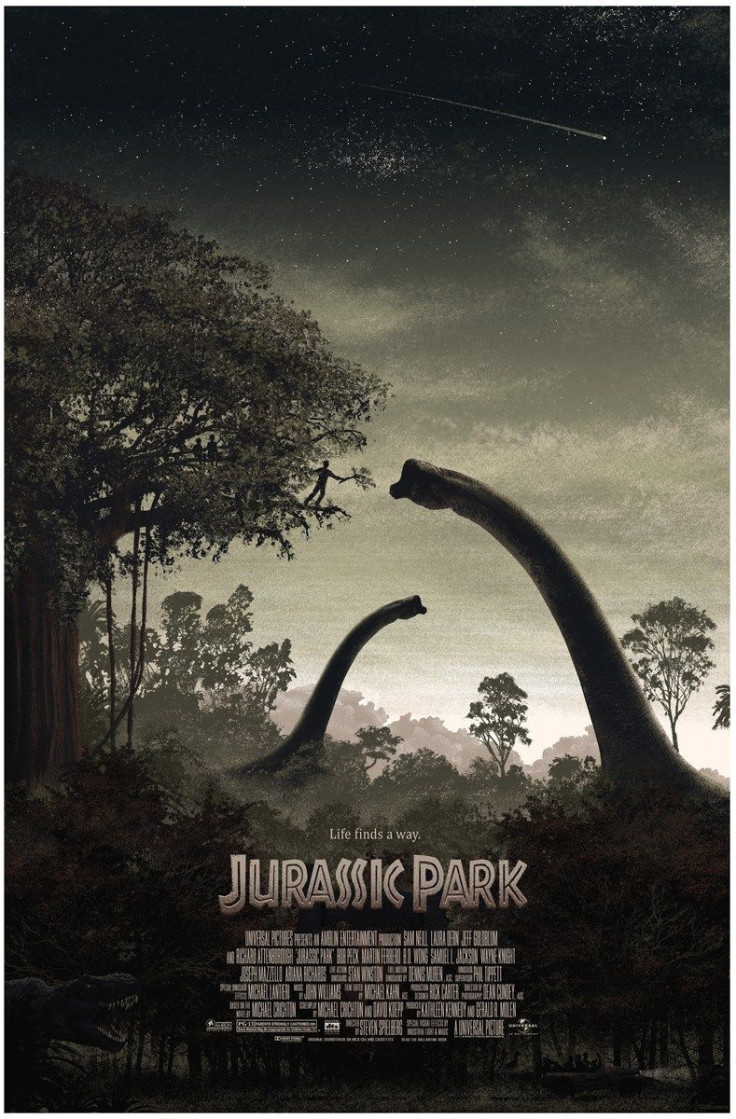

You’d know a Mondo poster if you’d seen one. Often exquisitely detailed, the right Mondo poster can reach into your memories and capture what the movie felt like inside your mind as you watched.

Like this Jurassic Park poster by JC Richard.

It’s more sentimental than literal, dramatizing the tranquility and wonder of that quiet moment nested in a loud film.

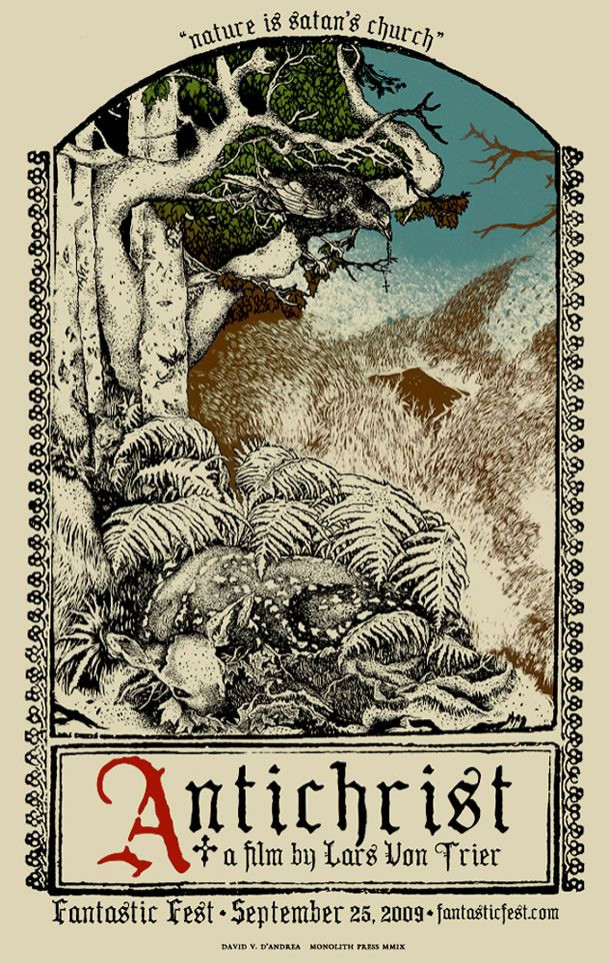

Or David D’Andrea’s Antichrist poster, which frames forest animals in a sinister archway. Some evil is outside of humans, too primal to be distinct but with its own arcane structure.

We spoke with Mondo co-founder and creative director Mitch Putnam about Mondo’s rapidly expanding role in modern poster collecting. “It originally started as a small store in the Alamo Drafthouse selling iron-on t-shirts,” Putnam says.

In 2005 Putnam and co-founder Rob Jones went to Alamo Drafthouse owner Tim League with a proposal to create posters for their Rolling Roadshow screenings. The small Texas theater chain had grown a substantial following with elaborate screenings like Lord of the Rings with all seven daily Hobbit meals, Close Encounters of the Third Kind at Devil’s Tower and the fire-breathing Robosaurus in the parking lot for the premiere of Transformers.

They started doing posters for individual screenings, with just a few event releases a year. But soon Mondo was focused more and more on working with studios and creating licensed artwork. “In 2010 we did a big Star Wars series and that was kind of what put us on the map and what made collectors recognize what we were doing in a big way,” Putnam said.

Rather than rely on the aesthetic judgment of movie marketing departments, Mondo posters combines the personal attachment many people have to their favorite movies with a contemporary eye. “Rob Jones and I come from the world of concert posters,” Putnam said. “So that's why a lot of the artists that we use came from that world as well.”

The typical Mondo poster begins with them approaching an artist with a movie title and nothing more. “We let them come up with the initial options as far as pencil sketches. And if we like things from there we take it to final,” Putnam said. “Generally we like to let our artists have a lot of creative freedom. And we have found over a lot of years of doing this that if you let the artists come up with their own interpretation of the film a lot of times you get something better than trying to predict what they would do.”

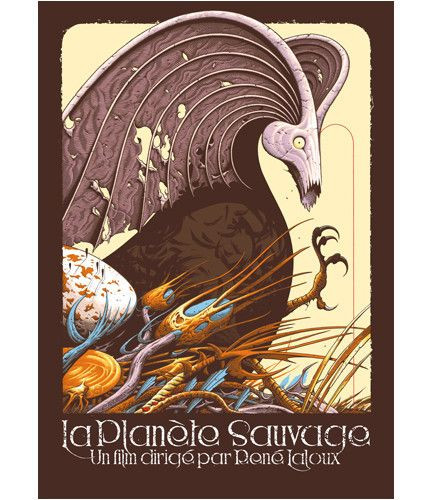

“ Back to the Future, Jurassic Park, E.T., things from that era are generally the properties that we see the biggest response on,” Putnam said. “That said, we’ve been really lucky with our fans. They are educated in the film world. So we can present strange, independent films that we’re big fans of and they’re completely receptive to it.” For every Star Wars there’s a Basket Case, Fantastic Planet or Battle for the Planet of the Apes.

Putnam cites Mondo’s close connection between fans and artists. “I think half the reason people love our posters is that people love the films that we make posters for. But I also think that we have developed a very strong relationship between our fans and the artists we work with. So many times when we do a poster a lot of the people are interested in the posters for the artist that worked on them.”

This is a major departure from traditional movie poster collecting. Today only a handful of famous poster artists, like Saul Bass and Drew Struzan, may be familiar to the general public. Most poster artists, especially from the early days of Hollywood, toiled in utter obscurity. “We probably know more about who built the pyramids than who painted posters in 1920s Hollywood,” Hershenson said.

In contrast, Mondo has developed a stable of return artists. Names like Olly Moss, Aaron Horkey, Martin Ansin, Randy Ortiz, Laurent Durieux and Tyler Stout have their own fandoms. For Putnam, an essential part of their success has been giving them the room to take stylistic and compositional risks. “I don't think we have a house style. I think we have house standards,” he said.

Between the online market in classic movie posters and the emerging limited edition market for original work, movie poster collecting is more vibrant than ever. The poster market is always a balance of subjective taste, nostalgic attachment and sheer commerce, but no matter which way the balance swings movie posters will always remain an analog redoubt from our digital world.

![[EG April 19] Best 'Stardew Valley' Mods That Will Change](https://d.player.one/en/full/226012/eg-april-19-best-stardew-valley-mods-that-will-change.png?w=380&h=275&f=955520b8313253ee3c39c791f6210f38)