In December 1994 Thomas J. Mosser, a public relations executive, opened a package that had been sitting on his kitchen table since the day before. It exploded, blowing out the windows on the first floor of his North Caldwell, N.J. home. Mosser was the third person killed by Ted Kaczynski — the “Unabomber” who’d detonated over a dozen bombs around the country since 1978. Desperate, the FBI pursued every possible lead, including, as newly obtained documents (available at Muckrock) show, Dungeons & Dragons players.

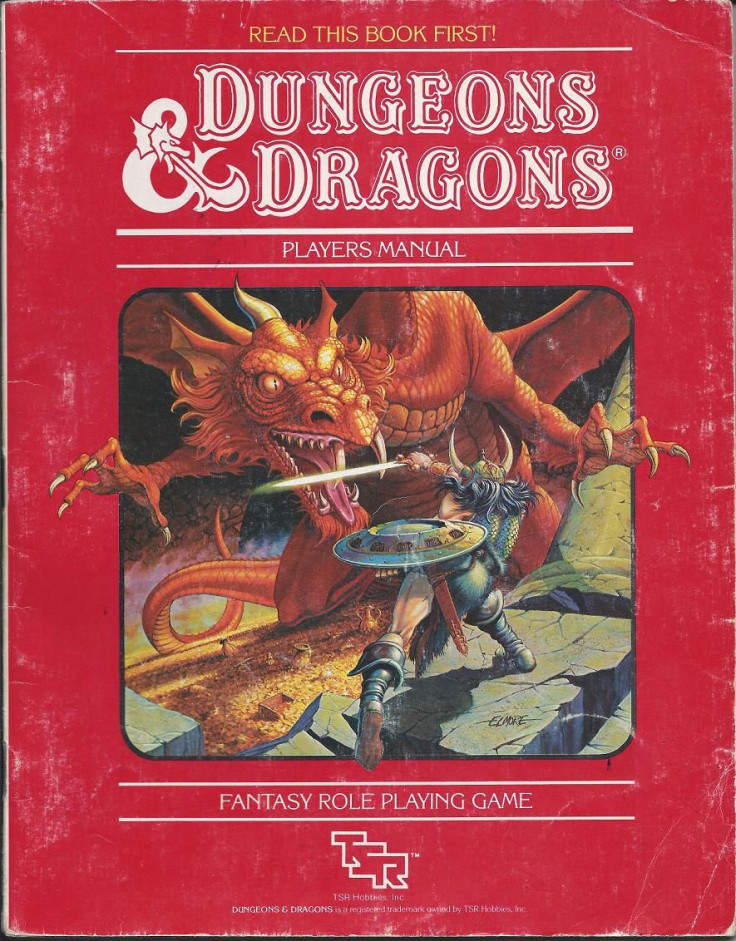

Almost four months later, in March 1995, the FBI reached out to an employee of TSR Inc. in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. TSR, founded in 1973 by Gary Gygax and Don Kaye to sell their self-published tactical and fantasy tabletop games — most famously Dungeons & Dragons — had fallen upon hard times by the mid-90s, losing out to upstart competitors like Wizards of the Coast (who would eventually buy TSR and Dungeons & Dragons in 1997).

The FBI report, obtained by criminal justice reporter C.J. Ciaramella, is heavily redacted, so it’s unclear what prompted them to chase the Unabomber into the halls of TSR. However, the first report describes the agency's internal source, a TSR employee, providing them with everything he knew about a specific tabletop gaming group (that may have included another TSR employee).

When the group learned that the FBI was snooping around TSR, they freaked. “Many of the members became paranoid and began pointing fingers at one another,” the FBI report reads. One redacted name even told the FBI “that he is quite sure that some of the members of the group fantasized about the possibility that maybe one of their members was responsible for the bombings.”

Further interviews suggest the FBI weren’t so convinced. The last (unredacted) word is given to an unnamed source, who told the FBI “the nature of their gaming activities and the fact that many gaming enthusiasts are also conspiracy theorists probably led to much of the finger-pointing.”

In a memo dated more than a month later, an FBI agent provided a fairly comprehensive summary of the founding of the state of tabletop role-playing, including a survey of TSR’s history. It provides a fascinating look at how law enforcement worked to understand the Dungeons & Dragons subculture, complete with descriptions of the Gen Con gaming convention, “miniature figures” and psychological profiling notes like “TSR has an extremely high concentration of very intelligent persons in employment.”

“War gaming and fantasy role playing differ in that war gaming involves a reenactment of historical wars and fantasy role playing involves adventures of fictional scenarios and characters,” the FBI writes. “Often they will live frugally to support the cost of the war gaming hobby. REDACTED REDACTED further advised that the typical war gaming enthusiast is overweight and not neat in appearance.”

But their most incendiary judgments were reserved for Gygax himself. “GYGAX spent his money frivolously,” the FBI memo records a source telling them. “GYGAX was involved in an unpleasant divorce and REDACTED further advised that GYGAX was a drug abuser.” The source went on to tell the FBI that he or she found Gygax “eccentric and frightening.”

In their assessment, Gygax would have been “extremely uncooperative” with any investigation, partially because of his Libertarian Party affiliation. Even trickier, from the FBI’s perspective, was Gygax’s coterie of war gamers, who they described as “very loyal to one another,” warning other agents that sources should be “selected carefully so that the investigation is not jeopardized.” Their biggest fear was that their investigation “could easily end up posted on the Internet system.” Some things never change.

The same detailed memo is also the source for our only clues why the FBI suspected role-playing gamers of involvement with the Unabomber attacks. Agents seemed particularly interested in D&D players' reaction to one of the bomb housings. Sources within the community were shown photographs of the wooden box that detonated aboard an American Airlines flight in 1979. But no one within the sphere of the TSR investigation knew anything about the box or recognized the composite sketch the FBI provided of their suspect.

This wouldn’t be the first time the FBI treated tabletop role-playing communities as potential wellsprings of societal subversion and illegal conspiracy. In 1983, the FBI sent agents to Lake Geneva, Wisconsin to investigate cocaine trafficking. Though the operation mostly cast suspicion on a network of local bars and bartenders, Gygax got swept up along the way, brought to the FBI’s attention by “a reliable Milwaukee informant.” What this person told the FBI remains unknown; the original memo was heavily redacted before release. FBI agents instructed to “review corporate records for TSR Inc.” reported back in a later memo, which made no mention of anything untoward in the D&D company’s incorporation. The matter seemed to be closed.

Despite the underwhelming evidence for Dungeons & Dragons or TSR collusion in the Unabomber attacks, by late September 1995 the FBI had adopted an aggressive stance toward what they called internally “The Dungeons and Dragons Group.” The agency declared the group “ARMED AND DANGEROUS” and started compiling a list of players and peripheral players. It’s unclear whether this list encompassed D&D players generally, or just one group, but the FBI's particular interest in Gen Con suggests they were casting a very wide net.

While the FBI was busy listing nerds, the actual Unabomber made his move, demanding newspapers publish his manifesto, Industrial Society and Its Future. It outlines an anarcho-primitivist philosophy that attacks technology for both its corrosive effects on human relations and for developing the mechanisms that will cement this immiserating power structure in place, controlling the human response to an increasingly stressful and unpleasant environment, rather than targeting the root causes. Industrial Society and Its Future, which can be read in full, opens:

“The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race. They have greatly increased the life-expectancy of those of us who live in “advanced” countries, but they have destabilized society, have made life unfulfilling, have subjected human beings to indignities, have led to widespread psychological suffering (in the Third World to physical suffering as well) and have inflicted severe damage on the natural world. The continued development of technology will worsen the situation.”

Kaczynski’s manifesto, published one week before the FBI memo listing Dungeons & Dragons players, lead directly to his capture. The Unabomber’s brother, David, recognized Ted in the writing style. Kaczynski overstepped and got himself caught, independent of years of investigatory work.

While the FBI can’t be faulted for pursuing every lead, the heavily redacted documents — themselves a small slice of what appears to have been a significant investigation — leave the overwhelming impression of a pursuit made more for reasons of ideology and oddity than evidence. Government agencies have demonstrated a pattern of mistaking or construing fictional role-playing games for real threats. At Reason Ciaramella describes a Secret Service raid of Steve Jackson Games offices under the flimsy pretext that their cyberpunk game represented a “handbook for computer crime.”

Under the FBI’s spotlight, Gygax’s presumed uncooperativeness and the under-investigation gaming group’s entirely rational paranoia became further reason to pursue them. And while the months of undocumented investigatory work between the first and last memos leave room for all sorts of possible explanations, the FBI’s leap from one-on-one interviews to full-blown “ARMED AND DANGEROUS” enemy lists sure looks like a dangerous example of mission creep. Particularly since, with hindsight, we know the Unabomber was not a Dungeon Master.

Be wary FBI, lest in your pursuit of Chaotic Evil you find the Lawful Evil in your own heart.

![[EG April 19] Best 'Stardew Valley' Mods That Will Change](https://d.player.one/en/full/226012/eg-april-19-best-stardew-valley-mods-that-will-change.png?w=380&h=275&f=955520b8313253ee3c39c791f6210f38)