The first episode of Rick and Morty Season 3, “The Rickshank Redemption,” shows Rick at the height of his power. He escapes from the Galactic Federation installation where he was imprisoned at the end of Season 2, brings down the galactic government, kills the entire Council of Ricks and frees Earth from extraterrestrial authoritarianism. At the end he terrorizes Morty in the family garage with one resounding message: I will change the entire galaxy to suit my whims. “All you know is that you know nothing and he knows everything,” Morty says of Rick. By the end of the episode, Morty’s description of Rick as “like a demon or a super fucked-up god” feels apt.

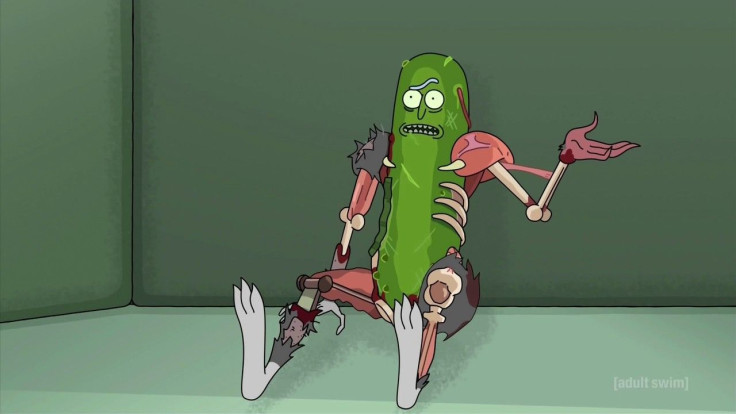

This week, in the latest episode of Rick and Morty Season 3, he turned himself into a pickle to get out of going to family therapy. Godlike powers, petty applications. Not only is “Pickle Rick” a sharp turn from Rick’s intergalactic machinations, but the episode ends with Rick just where he didn’t want to be: confronted by someone able to point out the limitations of his self-described mega genius. Dr. Wong (Susan Sarandon) pops the aura of control around Rick, revealing a bluff refusal to introspect fuelling his reality-altering actions. Coming after Rick’s greatest victory, “Pickle Rick” undermines its antihero as, or more, effectively (and a lot more efficiently) than prestige TV predecessors including Breaking Bad and The Sopranos.

Just as anti-war filmmakers have struggled to tell war stories without glorifying combat — French New Wave director François Truffaut famously claimed it was impossible — TV showrunners have grappled with our natural tendency to identify with a protagonist, no matter how repulsive. TV writers have pushed hard on the unlikable aspects of antiheroes like Tony Soprano and Walter White, applying a constant counter-pressure to the empathy that comes with our familiarity.

As the smartest man in the room, always ready with a quip, Rick is a natural target for audience identification. Not because we’re like Rick — we may all suspect we’re a Morty or Summer, maybe even a Jerry — but because we’d all like to be a Rick once in a while. Rick always gets what he wants and never loses a fight. He has grand adventures and makes fantastic discoveries. So what if he pays the price in an occasional onset of ennui and a persistent, semi-romantic alcoholism? This identification with Rick makes for strange reactions when he does terrible things. We want to see him triumph against the entire universe he’s enslaved in his car battery. It’s fun to see someone damn the consequences and leave some wreckage behind.

Different shows have tried different methods to combat or push against our overwhelming willingness to side with main characters who do terrible things. Breaking Bad tried to show the rippling effects of Walter White’s drug empire by smashing two planes together. Tony Sopranos’ behavior grew increasingly vicious, pushing away Carmela and Dr. Melfi, then sucking them back into his cycle of abuse. But there was nothing Tony or Walter could do to turn audiences wholly against them.

After five seasons trying to convince us Walter White was the villain, Breaking Bad gave up and deified him in the final episode. He dies triumphant, nested among meth manufacturing equipment, certain he’d secured a future for Skyler, Walter White Jr. and Jesse Pinkman. The Sopranos ended on blackness, into which we could project whatever consequences we’d choose for Tony.

But where Breaking Bad and The Sopranos primarily countered our protagonist identification by rubbing our noses in it, pushing their anti-heroes further and further into states of de-empathizing barbarism, Rick and Morty popped Rick’s god-like aura with a direct confrontation. Rick takes his best shot, describing Dr. Wong as an “agent of averageness” and therapy’s function as quieting a howling existential panic underlying our day-to-day lives, reinforcing placidity, “a state of mind we value in the animals we eat.” Dr. Wong’s response is not just an endorsement of the “repairing, maintaining and cleaning” work of therapy and mental health more broadly, but also exposes Rick to himself and to us:

“Rick, the only connection between your unquestionable intelligence and the sickness destroying your family is that everyone in your family use intelligence to justify sickness. You seem to alternate between viewing your own mind as an unstoppable force and an inescapable curse. And I think it’s because the only truly unapproachable concept for you is that it’s your mind, within your control. You chose to come here, you chose to talk, to belittle my vocation, just as you chose to become a pickle. You are the master of your universe and yet you are dripping with rat blood and feces, your enormous mind literally vegetating by your own hand.”

On The Sopranos, therapy is a narrative device that brings us closer to Tony. Therapy reveals to us that he has an interior life. But therapy took on a different narrative function in “Pickle Rick,” exposing Rick’s galaxy-altering actions as a willingness to alter the fate of millions to suit the contours of his comfort, because he refuses to change himself. It’s a moment that genuinely challenges our willingness to side with, even envy, antiheroes.