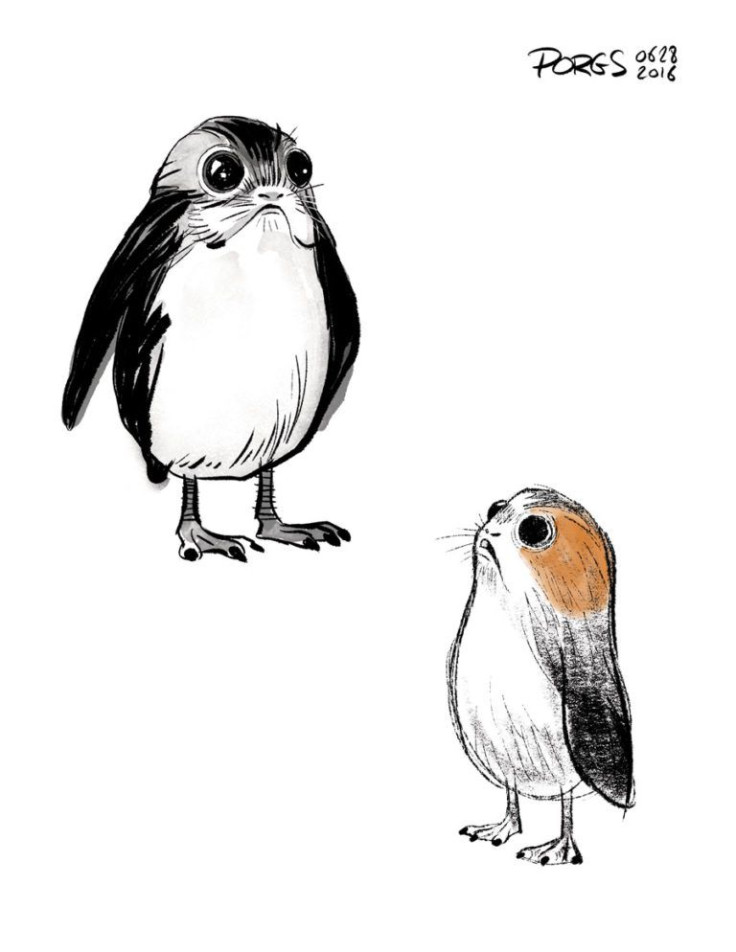

Disney/Lucasfilm introduced major advances in the science of cute, roly-poly creatures, which may finally hand humanity the weapons necessary to end our worldwide network’s infestation of Minions and sleepy puppies. On Thursday, the official Star Wars site revealed porgs, giving a name to an adorable little creature that first appeared, briefly (at 2:06), in the Star Wars: The Last Jedi behind-the-scenes reel shown at the D23 Expo. Porgs look like a puffin (the original inspiration), with the head of an otter. Ahch-To, where Rey will spend much of The Last Jedi training with Luke Skywalker, is swarming with the things. And soon the toy shelves will be too. We’re getting plush porgs and porglets at least, but porgs also seem like natural candidates for the Furby and/or BB-8 Sphero treatment. But barring nuclear war, climate-change induced societal collapse, superplague, rogue AI, human-greed induced economic and subsequent societal collapse, bolide impact, or supervolcano, Disney will likely be in a condition to think much, much bigger than toys in the coming years. This begs the question: When will a porg pet exist? And what Star Wars “Episode” will be out in theaters when it does?

A true porg pet, released by Disney, will require both significant genetic engineering advances and a massive cultural shift. Robotics is another option, but where to draw the line between toys masquerading pets — like the PLEO — and the real thing? Let’s shoot for something with a heartbeat first.

The first half of the equation, genetic engineering advances, will arrive speedily. The price of sequencing DNA has dropped at a rate Forbes described as “1,000 times more than Moore’s Law,” with full genome sequencing now under $1,000. That price is on its way to $100. But unlike the computation advantages Moore’s Law is meant to reflect, genome sequencing isn’t the measure that will ever get us to pet porgs.

Actually understanding the DNA sequences involves revealing the full function of genes: the units of DNA that lead to hereditarily passed traits and features, including behavior, development, body appearance and internal chemistry. This could be a far more daunting task than transcribing the nucleotides of the full DNA strand. For one, genes tend to have multiple, interlocking or overlapping functions. There doesn't seem to be discrete genes with one-to-one correspondences to features, except in rare instances. Behavior is even more complicated. We’re unlikely to just stumble upon the gene for “never bites a kid.” It doesn’t help that geneticists are discovering just how prevalent mutations are in the typical genome, meaning the same gene in me may not have the same DNA in yours.

Of course, incomplete knowledge of gene outcomes isn’t slowing anyone down. The genes we do understand are quickly commercialized, resulting in hypoallergenic pets, pre-plucked chickens, glow-in-the-dark everything and an increasingly refined understanding of speciation and inducing genetic change in animals. CRISPR, a technology based on the workings of a protein that can be modified to snip out and replace precise segments of DNA, is already revolutionizing this kind of gene-by-gene modification. Editing multiple modifications in concert to create a new species of pet is an inevitable byproduct of the breakthrough that’s already popping up in the academic literature. “Multiple guide sequences can be encoded into a single CRISPR array to enable simultaneous editing of several sites within the mammalian genome, demonstrating easy programmability and wide applicability of the RNA-guided nuclease technology,” the abstract for a 2013 paper from MIT’s Zhang Lab reads. Even with the immense difficulty in rewriting multiple genes to form a coherent new set of speciated phenotypes, we’re not that far from Disney accidentally gene driving a penguin species, creating a continent full of porgs and a hell of an interesting PR disaster.

The bigger obstacle to real-life porgs isn’t inventing the technology to create them, but the capitalistic will to do so. For now, genetic engineering, speciation included, is primarily directed at diseases and modifying existing organisms — designer babies, teacup elephants — rather than building whole genomes or chimeras. Outside of a narrow band of research, genetic modification remains legally and ethically tricky. George W. Bush famously denounced human-animal hybrids in 2006, leading inevitably to tens of thousands of people watching Splice, the poor bastards. Why the hell would Disney ever wade into that mess?

The answer is likely: they won’t. But there is a way to get to living, breathing porgs eventually and it runs right through robots. The most likely scenario for a porg pet, as much as it may seem like a cop-out, is a robo-porg. The subtle mechanical and sensor capacities required for contests like the DARPA Robotics Challenge have been roughly doubling in capability every two years, suggesting animal-like consumer robotics could be fairly convincing by the time Star Wars: Episode XII drops in 2027 (assuming a Star Wars Episode every two years, with an extra two year off after Star Wars: Episode IX in 2019). But while iterative, Furby-like releases might one day be sufficiently complex to trick us into believing we’re interacting with a real animal, that’s not quite good enough.

A robot porg will need a robot porg brain, capable of the complex behaviors we expect from cats and dogs, rather than a pre-programmed instruction set. The OpenWorm project has already simulated the full 302-neuron brain of a nematode worm. OpenWorm geneticist David Dalrymple believes full “cellular level emulation of the human brain,” with its 85 billion neurons, will be possible by approximately 2070. That would involve a rate that doubles the number of neurons we can simulate every other year. A software mouse brain, with its 71 million neurons, would be achievable by 2030 on this highly conjectural scale. And what a coincidence: io9’s future predictions roundup pegs 2030 as the decade in which artificial brains will achieve an effective symbiosis with robotic avatars.

And here’s where the genetic engineering returns, because modified pets and other genetically modified biological forms aren’t likely to come in through the front door. It’s hard to go from Tamagotchi to living, squirming, fully-engineered creature. But what about a robot with a layer of living fur? Maybe the porgs soft, biological eyes aren’t as imminent, (this isn’t a Cronenberg movie ffs) but it’s easy to imagine cyborg-esque mods that acclimate people to increasingly biological robots, even on the consumer level.

Assuming porgs become the Star Wars series’ chocobo, the technology could be in place for something very like a porg pet sometime in the 2030s. As robotics gets squishier, so will the products in our home, slowly acculturating us to full-fledged engineered pets in the subsequent years. You could be walking your pet porg in time for 2039’s Star Wars: Episode XX. Unless everyone hates the damn things when Star Wars: The Last Jedi comes out in theaters Dec. 15.

- Pushes each character forward

- Amazing ship battles

- I love Kylo Ren

- Kylo Ren shirtless

- Kylo Ren

- Luke Skywalker has the most astonishing arc in mainstream hero history

- That one Leia moment no one liked, but they're wrong

- Plot contrivances to position characters

- A few clunky lines

- Canto Bight action sequences feels superfluous

![[EG April 19] Best 'Stardew Valley' Mods That Will Change](https://d.player.one/en/full/226012/eg-april-19-best-stardew-valley-mods-that-will-change.png?w=380&h=275&f=955520b8313253ee3c39c791f6210f38)