My general assessment of 2017’s It is a positive one. Upon initial viewing, I tried my best to temper my lack of familiarity with the source material (both the iconic Stephen King novel and the now infamous TV miniseries, of which I’ve seen bits and pieces) with a steadfast adherence to its merits as a film, not an adaptation. This approach was important to me, not merely because I can’t be bothered to sift through King’s 900-plus pages of yokel Lovecraftian drivel, but because I believe the Age of Nostalgia has slackened our sense of proper evaluation.

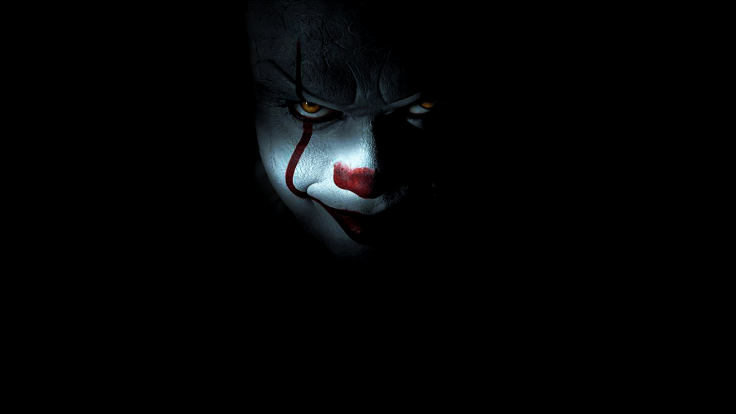

Once again I liked It, very much in fact, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t call it safe. Everything is safe. Even movies adapted from books about interdimensional clown deities that feed off the fear of children have to adhere to a rigid three-act structure, the inclusion of contemporary pop tunes, and tension splicing humor. Regardless of the notably weird reputation that proceeds the novel, I, who never even read the thing, was uncomfortably aware of a sense of hesitation throughout the film. I couldn’t escape the feeling that none of this was supposed to feel so digestible. The narrative dares to toy with salient, often uncomfortable themes, but doesn’t bother to say anything. It amounts to little more than a jump scare laden Stranger Things, with a bigger budget to boot.

For clarification's sake, at the risk of being redundant: this is an indictment of creative cowardice, the novel notwithstanding. Take Peter Jackson’s Lord of The Rings trilogy and Kubrick’s The Shining – one a "faithful" adaption, one a "good" adaptation. Now when distinguishing “faithful” adaptations from “good” adaptations, we have to discuss style and perspective, two attributes utterly annihilated by the franchise infection plaguing the industry for more than two decades.

In either case, the filmmaker (that’s important) utilized great stories to express sentiments and ideas. Not in some didactic way, but you got the sense each director had reasons beyond industry trends for telling these stories. Take Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings, orchestrating a “faithful adaptation” has less to do with homage and more to do with transcription. As for Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, it borrows basic ideas and imagery from the novel to fortify a message unique and irrespective of Stephen King’s. From the motifs to the visuals,The Shining and The Lord of the Rings are almost as synonymous with their filmmakers as they are for their authors.Any good adaptation works regardless of whatever cultural impact its origin engenders.

The works of Tolkien, George RR Martin and perhaps most famously JK Rowling managed to capture audiences across mediums because of exceptionally crafted foundations. The job of the adapter isn’t to “preach to the choir” as it were ( Warcraft ), nor is it to forgo core elements of its source material to convert the impartial (The Dark Tower).

I can’t speak to Cary Fukunaga’s initial vision of the project, except to assume his departure from It avails my point. I would still recommend you check out the film we ended up with at your local cinema. It is good, but it should’ve been great.