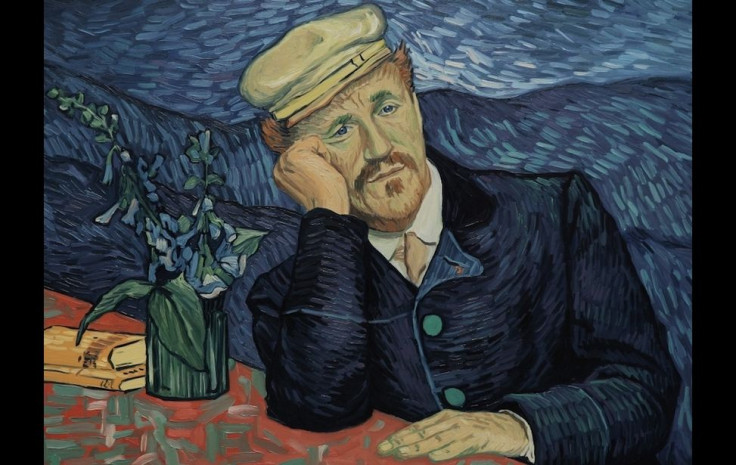

I recently reviewed the film, Loving Vincent, Dorota Kobeila and Hugh Welchman’s innovative animated homage to the tortured post-impressionist painter, Vincent Van Gogh. The film’s narrative focuses on the mysterious circumstances surrounding the “eccentric” dutchman’s death, but any effective Van Gogh biopic can’t help but brush against the grim irony that is his posthumous success. All of the things that make Van Gogh’s work (and behavior) compelling to contemporary observers deemed it and him a failed pariah in most of the social and artistic circles of his day – he was out of rhythm. In addition to defining the modern art aesthetic, Van Gogh’s well-documented mental deterioration and ultimate suicide were seminal in romanticizing the kind of melancholy mythology we have come to expect from any worthwhile “genius.”

From Virginia Woolf to Kurt Cobain to Heath Ledger, we love to believe that mastery comes with a price of one’s soul. Initially viewed as the flipside of the coin for the “great artist,” a troubled mind has over time become its unassailable companion. This has burdened mental illness with a new kind of stigma, one every bit as pernicious as the antiquated mindset that led Van Gogh to suicide. Before I attempt to make the case that the correlation between madness and genius is both regressive and detrimental, I want to acknowledge that the genetic link between mental illness and creativity cannot be easily dismissed. Either way, I believe marrying brilliance and misery is a trope worth trying to dispel.

Our misguided preoccupation with torment is even realized in our fiction, where the Byronic hero occupies most of the iconic works of the 21st century. Arguably the most enduring superhero of our time, Batman, is one defined by his psychological hangups. The fact that he is frequently cited as the most “compelling” comic book character feeds into the misconception that tragedy, as a rule, equals interesting – that trauma is assured to give rise to some kind of alluring charm. This is a poisonous archetype to emulate.

As it relates to Van Gogh, as evident by his numerous letters, whatever benefits afforded him by his madness was certainly eclipsed by its endless adverse effects. In fact, I might even call it a hindrance as opposed to some kind of morbid exchange. I believe the notion that Van Gogh, or any acclaimed artist, needs despair to create to be a fallacy – a fallacy we should all be making an effort to repudiate at every turn.

If it is true that psychiatric medication in some ways blunts artistic sensibilities, we should take all the energy we exert toward idealizing mental illness and devote it toward finding a way to make stability and virtuosity congruent. Comedian Chris Gethard on the topic once said: “If you went to a dentist, and you didn’t like the dentist’s personality, you wouldn't let all your teeth rot out.”

We should never give any sick person the impression that their sickness is in any way integral to the creative process. Mental illness is responsible for 3,400 deaths a year and it’s time we stop glamorizing it and start treating it like the unyielding evil it really is.