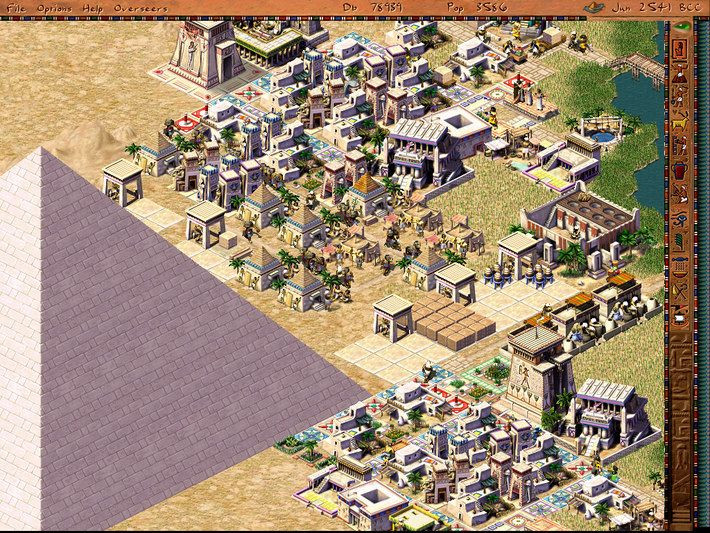

Cities: Skylines sold a million copies in a little over a month. It’s a dramatic return to form for the genre of city-building games. If you played PC games in the 1990s, you remember the genre’s heyday. SimCity, of course, was always the biggest name, and the game Cities: Skylines ultimately takes after. However, SimCity was far from the only city-building simulation. The City Building Series from Impressions Games ignored a modern setting, instead releasing a series of city builders set in the ancient era. Caesar, Pharaoh, Zeus, Emperor—for years, the games thrived… until they disappeared.

Now, in 2015, city building games—long in a slump—are in the spotlight again, thanks to the immense success of Cities: Skylines. The modern-era city building sim, developed by Colossal Order and published by the exceptional Paradox Interactive, shows city sims and urban development games can still be vibrant and exciting—and that they can be produced by a small team. That brings back hope for the other side of city simulation games, the ancient era ones. iDigitalTimes recently spoke with Chris Beatrice, the CEO of Tilted Mill Entertainment and former lead designer of many of the games in the Impressions City Building Series, to take a look at the genre of ancient city builders—why it thrived, what went wrong and whether building digital versions of ancient cities has a future.

The Other City Building Games

The Golden Age Of Ancient City Builders

In 1992, Sierra Entertainment published Caesar. Released three years after SimCity, the game tasks players with constructing ancient Roman cities. The release took cues from both SimCity and Civilization.

“The Impressions city-building games really brought together two very appealing aspects of games from that era: hardcore historic-based strategy games like Civilization, and sims like SimCity,” said Beatrice, who served as art director on Caesar II and in lead design roles on the following games in the series. “Games like ours were kind of outliers in the strategy genre. Even being real time in strategy games was somewhat of an anomaly at the time.”

The series evolved with 1995’s Caesar II and 1998’s Caesar III, but it was 1999’s Pharaoh that really shook up the series by adding monument construction. No longer were armchair praetors onlybuilding efficient, prosperous cities. Instead, wannabe Pharaohs had to do all that—and also build pyramids.

“The monument construction in Pharaoh was so obvious it basically had to be done,” Beatrice said. “One problem we always had with city-building games was that, with a sim, it’s not really obvious what it means to ‘win.’ We had those ratings targets [for Prosperity, Culture, Peace and Favor] in Caesar III, which are okay, but somewhat anti-climactic. If instead you can see your entire city crawling with activity, all feeding this massive monument, suddenly it all takes on great meaning.”

For Zeus: Master of Olympus and Poseidon: Master of Atlantis, released in 2000 and 2001 respectively, the series embraced its inherent unrealism.

“With Zeus, it was about understanding what most people associate with the given setting. For ancient Greece, it’s the Greek gods and their mythology,” Beatrice said.

The game also added a colony system: Instead of building a different city in each mission of the campaign, players would build the same city to higher and higher levels, with occasional excursions into remote colony cities that could provide needed trade goods.

Between that and the addition of quests, monsters and a loose storyline, the Greece- and Atlantis-focused games took the series to its heights.

“With the sequels, we were able to fine-tune, improve upon and enhance the core aspects of the gameplay—farming, harvesting, storage and delivery,” Beatrice said.

Emperor: Rise of the Middle Kingdom (2002) took the series to ancient China and refined it further, adding better graphics, more complex systems and—finally—multiplayer.

Then the whole thing died.

A City With No Simulations In It

“I think city-building games went through an identity crisis,” Beatrice said. “They tried to keep up with the best, most advanced visuals, despite the fact that the budgets weren’t there to support that. In that process the simple core game dynamics, and the focus on gameplay in general were underserved. The nature of city-building gameplay in general is not conducive to 3D (at least it’s not in really helped by it).”

Sierra Entertainment, parent company of Impressions Games, was acquired by Vivendi in the early 2000s and the conglomerate shut the studio down in 2004. It wasn’t the end of the City Building Series, but it was the end of their golden age.

The rise of 3D gaming in the '90s crushed out the mid-budget game that once formed a large chunk of the market. The increasing cost of graphics production and the consolidated retail market—at that time the only real outlet for sales of computer games—made mid-level games a less viable proposition as triple-A titles took over.

When Impressions closed in 2004, Beatrice and many other Impressions alumni formed a new company, Tilted Mill Entertainment, to continue the former developers’ mission. Their first two games revisited the City Building series, first indirectly with Children of the Nile (2004)—a spiritual successor to Pharaoh—and then directly with Caesar IV (2006). Both games received a relatively mixed critical reception and lackluster sales, a far cry from the huge success of the earlier games, some of which sold more than a million copies.

“I think there are two different stories there. With CotN we really wanted to do something new and different, and in a few fundamental ways that game broke some of the understood ‘rules’ about how these games worked,” Beatrice said. “We did not do a very good job of teaching players the game, of making sure players weren’t assuming things worked a certain way. But even if we had done that better, the organic nature of the gameplay—which I think was a huge accomplishment—makes it very difficult to communicate to players exactly what is going on in the game, which the Impressions games did so brilliantly.”

CotN was more realistic than the other City Builders, which traded realism for elegant but artificial systems and ease of gameplay. CotN more realistically simulated ancient economics, but Beatrice admits the realism narrowed the game’s audience to a band of core strategy gamers.

“For a big chunk of gamers, that [realism] is a little more fun in theory than in practice,” he explained. And the game suffered from independent distribution in an era before that was truly viable.

Caesar IV suffered the opposite problem: It succumbed to the push for graphics. Caesar IV didn’t stay “laser-focused on gameplay, gameplay, gameplay,” Beatrice said. “This was a time when most publishers were judging games based on screenshots—even though players weren’t really doing that.”

Both games suffered from the mid-00s consolidation of the games industry, and the general slowdown in PC gaming at the time.

And that’s been the end of it. Although Tilted Mill has released a number of successful games since Caesar IV, the company hasn’t made another ancient-era city builder. Neither has anyone else.

Yet.

The Indie Renaissance and the Future of City Building Series Games

The ancient-era city building genre is gone, but not forgotten. Caesar 3, Pharaoh, Cleopatra, Zeus & Poseidon are all among the top-selling and highest-rated games on GOG.com. The site is a digital distribution platform owned by CD Projekt Red, focusing on releasing classic (and modern) games DRM-free in formats that play on today’s computers. The City Building Series lives on there. To Beatrice, the series’ continued success, well over a decade since release, shows there’s still room in the market for this kind of game, and that high-end graphic are less important than ever.

“It’s kind of remarkable how similar the numbers and overall economics are to 20 years ago, at least within certain niches,” Beatrice said. “In the early 1990s, you could make a pretty good game with a small team and sell it yourself, and now thanks to new tools, digital distribution and social media, you can do that again.”

Small, hardcore, indie PC games are on the rise—just look at Crusader Kings 2, or, heck, Cities: Skylines, both million-sellers developed by small teams on reasonable budgets.

“What doesn’t work is the midrange $2 to $4 million hardcore PC game,” he explained. “That’s too much money to fund yourself (or easily with crowdfunding) and far too little to make a big AAA game.”

The dynamic of strategy games has changed too.

“Players don’t tolerate the kind of crap we used to put them through. It used to be okay if it took players several hours or even days to fully learn how to play a game. You paid $40 and were happy to invest the time so you could get hundreds of hours of enjoyment out of it. It was kind of a badge of honor to thoroughly understand how a complex strategy game worked. That is obviously still the case in some circles, but it’s not the norm,” he said.

Games now, Beatrice said, need to grab players immediately, citing online offerings like Cityville, which carefully curates even the first minute of gameplay.

The ancient city builder series may make a resurgence one day, and Beatrice hopes to return to it.

“I still hate modern settings for city builder games. I just can’t get into them. For me, the idea of city-building is synonymous with growing a civilization” he said.

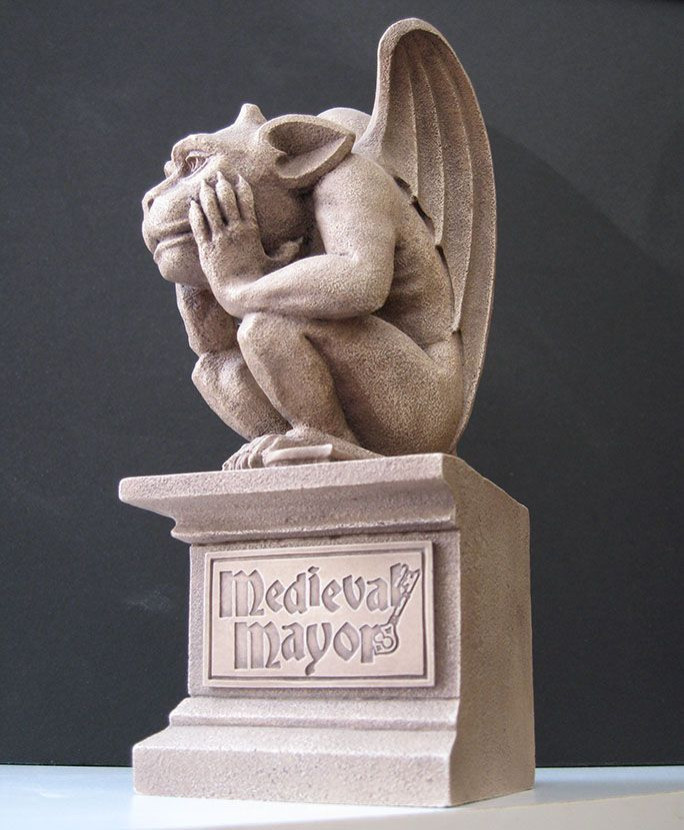

Tilted Mill has a few projects in pre-production, but nothing definitively announced. The studio’s Medieval Mayor, a medieval-era city building game that was backburnered after a few years of development, is one possibility. Beatrice adds the studio is also considering a sequel or remake of Hinterland or “some kind of fairy tale game.” But whatever the future holds, the golden age of city building games is gone—at least for now.